Nobody likes lag, especially not developers. When you type a character in a terminal or editor, you expect it to appear instantly. At Compyle, we spin up ephemeral cloud dev environments where an agent and a user share an IDE + terminal. So how can we make a remote sandbox feel local?

TL;DR: If you want low latency sandboxes, cut out the middlemen and put your servers next to your users.

The Naive Approach

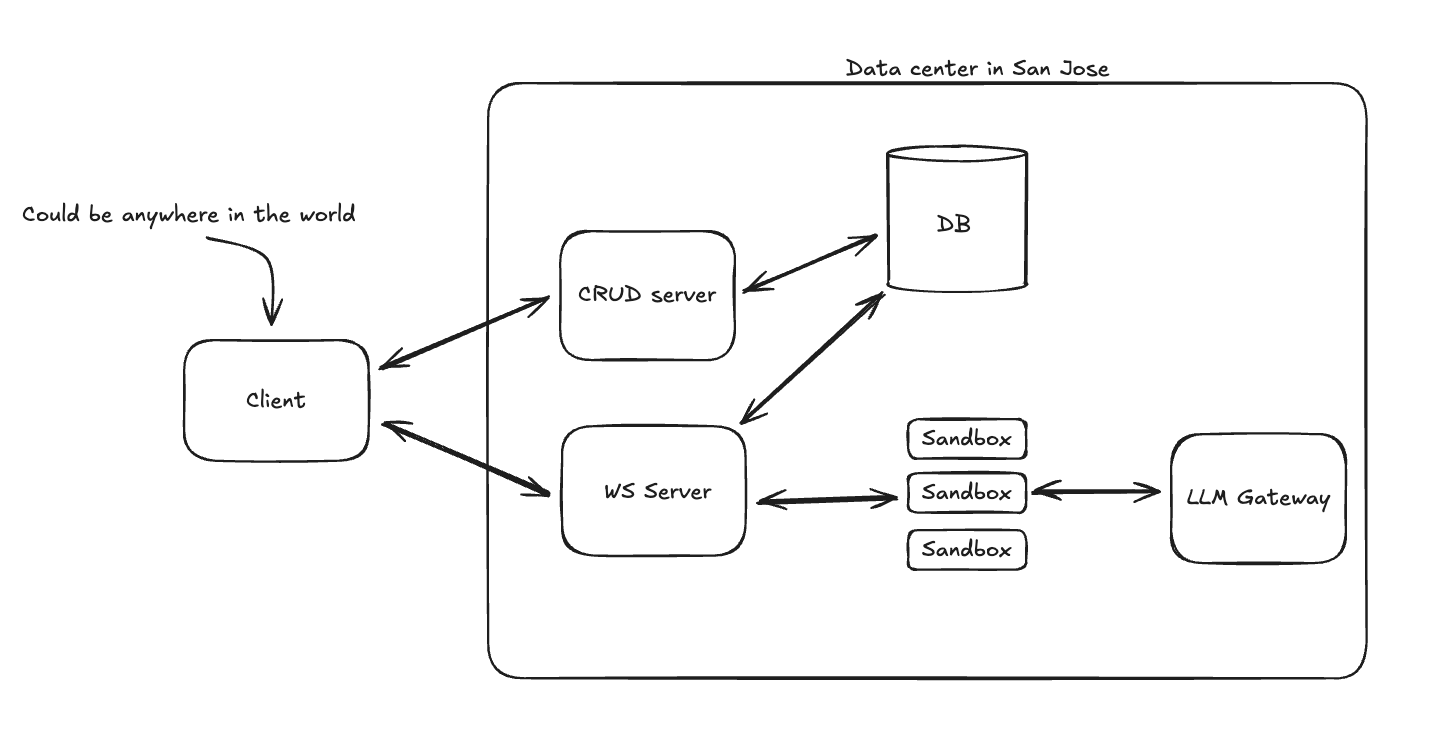

Here is what our initial architecture looked like:

The flow would be something like:

- User starts task

- We provision a new sandbox in our primary region

- We communicate with the agent through a socket server that handles authorization, routing requests to the correct sandbox, and persisting any messages the agent sends (we don’t want to give the sandbox any credentials).

There are three main concerns with running a coding agent sandbox.

- Startup time

- Latency

- Security

I can confidently say that this architecture does pretty poorly on the first two categories. Here’s the scorecard:

Startup time: bad (10-30 seconds)

While many sandbox companies advertise sub-second cold starts, this simply wasn’t the case for us. Our dockerfile is a few hundred megabytes and we attach an encrypted volume to each machine. In practice, machines took 10 seconds to start in the best case, and 30 seconds in the worst. That said, now is a good time to mention that we use fly.io for our sandboxes, and love it. More on this later.

With this approach, users are staring at a loading screen for 30 seconds before the agent’s first message would appear. Yikes.

Latency: also bad (>200ms)

We had two glaring issues on the latency front:

- Every request makes an extra network hop. Worse yet, for websocket connections we were stitching the client connection to the agent connection in the socket server, which had some overhead.

- Persistence was on the hot path between the agent and the client, so that extra network hop caused additional latency from any database queries done.

For the agent messages, an extra 150ms isn’t the end of the world because LLM calls make up the lion’s share of the gap between messages. The real issue is in the terminal and the IDE. It was about a 200ms lag between hitting a key and seeing the character in the terminal. Genuinely unbearable. Same for opening a file in the IDE.

Security: it’s fine

The agent wasn’t exposed to the public internet and doesn’t have any secrets. I’ll save security details for another time, though.

The point here is that this architecture does poorly on two of our three concerns; it’s painfully slow.

Fixing startup time: the warm pool

The startup time is pretty easy to fix. Rather than provision a new machine every time someone requests one, we can keep a warm pool. Now, a pool of machines sit at the ready, so every time a user starts a task, we simply send an http request to start the task.

Great! No more cold starts, so startup time goes from 30s → 50ms

This does not solve the latency issue, though.

Cutting out the middleman (and why I love fly.io)

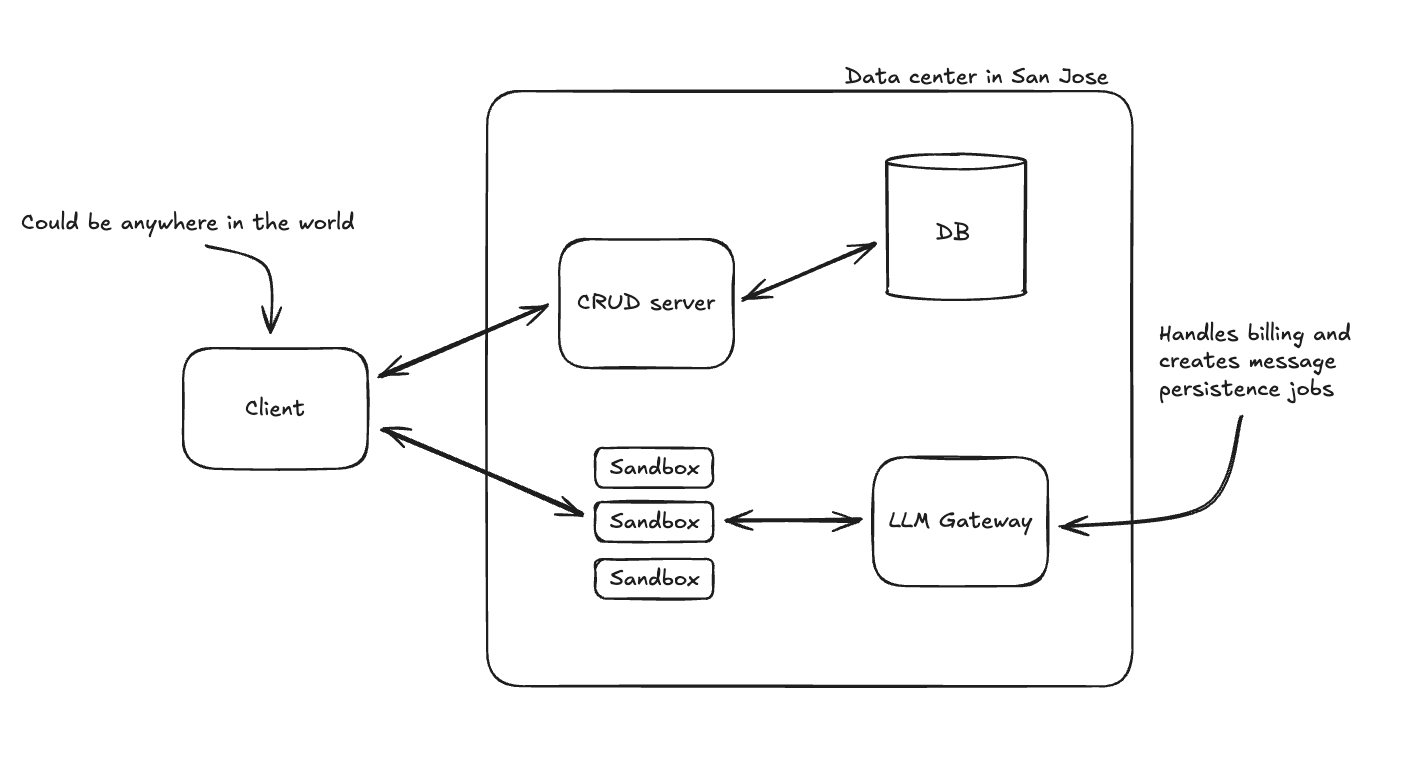

To remove that extra network hop, here’s the new architecture we went with:

Spoiler, this change was the biggest win performance wise, but also the biggest lift technically because our socket server had so many responsibilities:

- Authorization

- Billing and persistence for agent messages

- Routing requests to the correct machine

Each of these had to be addressed separately.

Authorization

Originally, we were authenticating users on the socket server, so each request made a database query. Since we are connecting directly to the machines now, a better approach is to create a JWT when the task is created, send it to the machine and the client, let the client connect directly to the machine. If the machine’s token doesn’t match, it’s an unauthorized request.

Billing and persistence

Originally, we would bill users on each request going through the socket server, and send an interrupt back to the agent if the user was out of credits. We have an LLM router that receives all of the same messages, so we moved the responsibility there, and let it return a 402 for the agent to handle when the user is out of credits. For message persistence, by making the agent the source of truth for messages, we could also accommodate the database’s message records only being eventually consistent. We batch process them in a separate queue worker so we don’t hammer the database.

Routing requests

Originally, our sandbox urls were formatted like <task_id>.machine.compyle.ai. We would do another database lookup to find the correct machine and use fly.io’s private network addresses to route the request by machine id from the socket server.

We switched the domain to use <machine_id>.sandbox.compyle.ai and adopted fly.io’s clever proxying mechanism, fly replay. Fly replay is a cool trick that allows servers to respond to http requests with a 307 and fly-replay header to signal fly’s network to bounce the request to the machine specified in the header. Crucially, Fly can cache that behavior so that the bounce only happens once. You can read more about it here.

At this point, the terminals and IDE were super fast for me, but I live in San Francisco, right by the data center in San Jose. For a user on the East coast (or elsewhere in the world), it was a different story. This is what the latency of a user typing ls -lsa into their terminal from Virginia would look like:

That’s an average 79ms roundtrip, and we can do better.

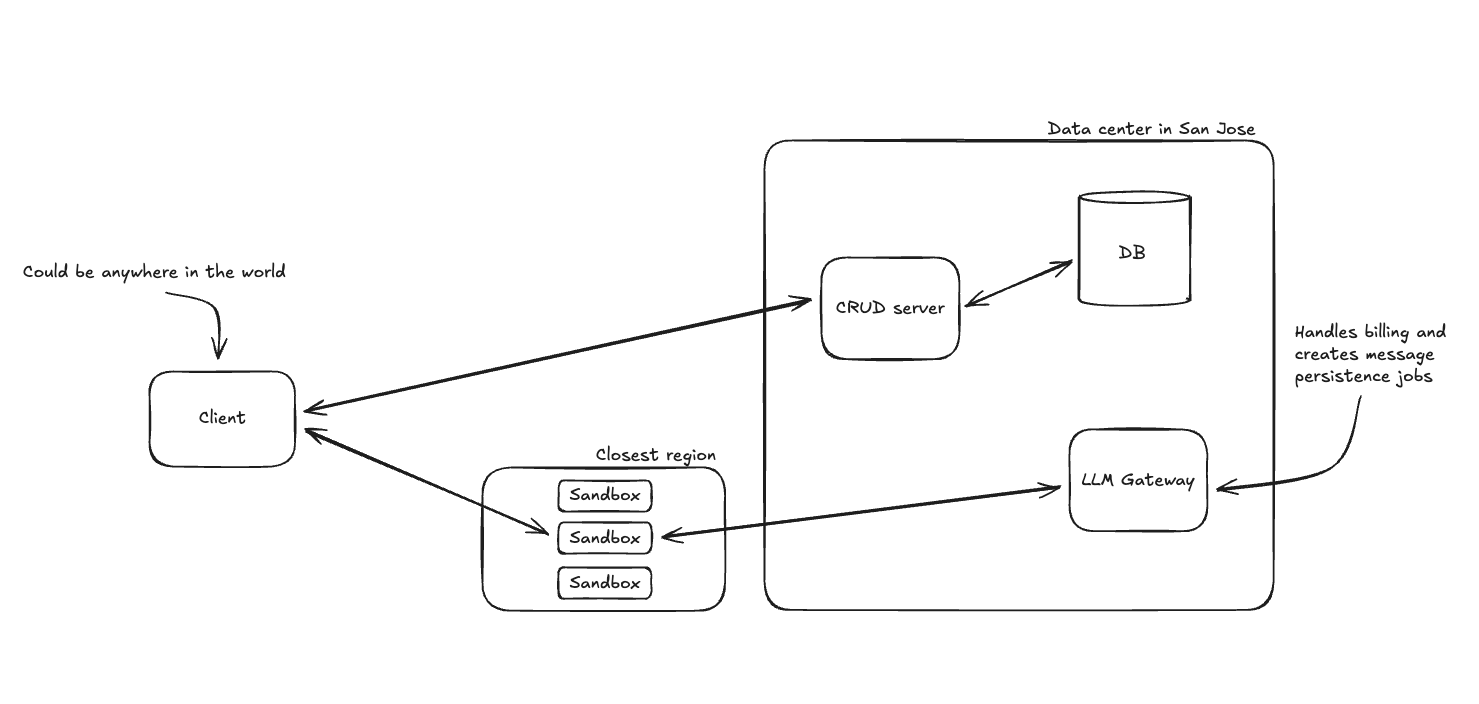

Multi-regional pool

If I’m in San Francisco, and I get the benefit of working on machines in San Jose, then why shouldn’t our users? The last unlock was moving our sandboxes to the closest region to our users. We still have to keep a warm pool, so instead of keeping one warm pool in San Jose, we now keep separate pools across the US, Europe, and Asia.

Here’s our architecture now:

And here’s what the latency looks like for a user typing ls -lsa into the terminal of a nearby sandbox:

That’s an average 14ms and that’s pretty good.

Final Results

Reducing terminal roundtrip time from >200ms to 14ms feels great, but real lesson here is a familiar one: simple solutions are best. Our final architecture has less infrastructure than our initial architecture. The biggest speedup came from deleting the socket servers and the code that lived on them. If you want to improve performance it’s often best to look for what you can remove.

Mark Nazzaro

Mark Nazzaro